Have you worked on some important goal for months and years, but didn’t make much headway, stayed at an average level? Fitness. Studies. Financial goals. A skill.

Few, on the other hand, achieve their goals in the same or shorter period.

Hard work is table stakes. You’ve to put in the hours if you’re chasing a big goal, but that alone, more often than not, is not sufficient.

Matthew Syed, in his book Bounce, gives example of how his mother’s typing speed hardly changed despite several years of practice:

My mother was a secretary for many years and, before embarking on her career, went on a course to learn how to type. After a few months of training she reached seventy words a minute, but then hit a plateau that lasted for the rest of her career.

She worked several hours every day for several years, and yet she stayed at the same level.

Sounds, familiar?

Why some people get stuck?

Simple. Because they’re not improving.

You don’t improve by doing the same thing again and again mechanically without raising the level of difficulty in your task. If Matthew Syed’s mother had shown the same intensity to improve after landing the job as she showed before, she would have reached an altogether different level.

A math formula to explain that hard work is necessary but…

You deposit Rs. 100,000/- in a fixed deposit with a bank.

Scenario I

Term of the deposit = 3 years

Interest rate = 7%

What amount will you get when you redeem the fixed deposit at the end of its term?

You’ll get Rs. 122,504/-.

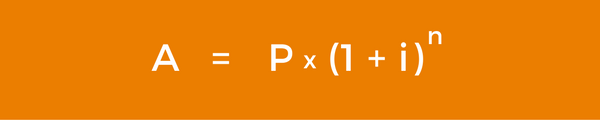

You can plug the values in compounding formula to make the above calculation.

Here ‘P’ is the amount at the starting point. It grows at an interest rate of ‘i’ per year for ‘n’ years to become ‘A’.

Scenario II

Now, what if, for some weird reasons, the bank offers zero interest rate and you’ve no option but to take it? Here,

Term of the deposit = 3 years

Interest rate = 0%

What amount will you get after 3 years?

You’ll get what you deposited, Rs. 100,000/-. You understand this, right?

Interest rate is nothing but improvement in the money you’ve put in. Zero interest rate means no improvement, which means your money remains at the same level despite working hard (3 years in the fixed deposit).

You may work hard for several years, but without improvement, you’ll stay at more or less the same level.

For Matthew Syed’s mother’s typing practice, ‘i’ was practically zero.

Scenario III

What if you keep Rs. 100,000/- at 7% interest rate for only 3 months? Here,

Term of the deposit = 3 months

Interest rate = 7%

At redemption, you’ll get Rs. 101,706/-, much less than Rs. 122,504/- you got after 3 years.

You may be improving, but if you don’t continue the work for long (only 3 months in this example), you won’t go too far.

If you combine the two lessons:

You need both hard work and improvement over considerable period of time, like in Scenario I, which yields the maximum amount of Rs. 122,504/-

Most understand what hard work is, and few of the motivated ones put in those hours month after month. However, an overwhelming majority doesn’t know how to keep improving beyond the initial phase. That’s the reason when we learn anything new, we make fast progress in the beginning and then plateau. (In the beginning, anything we do is an improvement.)

Compounding isn’t just a math formula. It’s a framework

Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, keeps itself on course by following a framework (or guiding light) whose important cog is obsession with customers. They know if they base their decisions on customers – and not competitors – their odds of drifting will be much less.

You too can make compounding formula a framework to avoid drifting.

When working on a challenging task, go back to the compounding formula multiple times and ask yourself: is the ‘i’ positive (which means you’re improving) and is ‘n’ significant (have I worked long – or hard – enough)?

This framework will help you:

- Increase your odds of succeeding in a challenging task

- Not waste months and years of hard work

Compounding explained through Stall Curve

In his book Great at Work, Morten T. Hansen describes how performance varies with practice through two curves:

‘Mindless Repetition’ curve shows how almost all of us practice – mindless repetition without focus on improvement. As a result, people stall at an average level. (Note that even in ‘Mindless Repetition’, you’ll show some improvement in the beginning if you start at a poor level.)

‘Learning Loop’ curve shows how improvements can take people to a very good level. But, barring handful, even those who look for improvements eventually stall (blue dotted line).

Morten cites the example of teachers from North California to highlight how fast they reach stall point:

…A large-scale study in North Carolina, for example, showed that teachers improved from zero to two years of teaching experience, but then stalled. Teachers with twenty-seven years of experience (that’s more than 40,000 hours of practice) were not much more effective than those with two years in improving students’ achievement, as measured by their proficiency in English and Math.

Think of it: not much difference between teachers with twenty-seven and two years of experience. Those with twenty-seven years of experience stalled after two years and stayed at more or less the same level for the next twenty-five years.

Déjà vu. Typing example we covered earlier.

Top performers, however, push beyond the stall point (the dotted extension of ‘Learning Loop’). They’ve the motivation to further refine their skill – which BTW is discomforting (more on this later in the post) – to reach extraordinary level.

To quote Magnus Carlsen, the chess phenom who holds the record of highest ever peak rating of 2,882 points, from Great at Work:

I am still far away from really knowing chess, really. There is still much I can learn, and there is much I still don’t understand. And this makes me motivated to keep going, to understand more and more and develop myself.

Arguably the best ever chess player, and he still wants to improve. That’s probably the reason why he has reached the level he is at.

If you read interviews of Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic, the best three tennis players of all time who incidentally are contemporaries, you’ll see multiple instances of them crediting each other for the level they’ve reached. In other words, mutual competitiveness has forced them to improve their games further. Without someone pushing at their heals, they could’ve stalled too (and still be world # 1). I would argue that Federer plateaued after his unchallenged dominance from 2003 to 2007, and was forced to move beyond stall point after Nadal and then Djokovic challenged him.

Why we stall?

Why we stall. Or why we don’t improve (‘i’ = 0)?

1. Many think mindless repetition is enough

Yes, many associate expertise gained or progress made toward a goal with number of hours spent on that activity. They think mindless repetition is the way to master something. They think their level will rise as they spend more time on that activity, but it doesn’t. (Few people may unconsciously bring in few improvements, thereby raising the level little bit, but otherwise just spending time doesn’t help much.)

Because they don’t even know that they’ve to actively find areas of improvement and then work on them in order to master something, they simply go through the motions. They put in the hours, but don’t progress.

2. Improvement entails discomfort

Always.

Let’s understand this through an example.

You decide to bulk your muscles up. You join a gym and start lifting weights. You get comfortable at a particular weight and then increase it further. Discomfort for few days and then you get comfortable at the new weight. This cycle repeats, and with each cycle, you get comfortable at a level higher than earlier. However, if you don’t increase the weight, you get into the rut of repetitive stuff (lifting the weight you’re comfortable with) where you aren’t tested, and resultantly your muscles stay at the same level.

Every time you increase the weight (this is akin to improvement), you’re discomforted lifting the new weight because you’re not used to it. This discomfort pulls us back, stops us from continuing to improve.

This discomfort, BTW, isn’t limited to physical activities such as lifting weights. Even in less physical or completely mental activities, you’ll face discomfort if you decide to improve. Try writing if you’re not used to it. Many learners of English language face discomfort while speaking English (and they switch back to their first language on and off, slowing their progress).

You’ve got to be motivated to keep working despite the discomfort.

What happens in reality is that vast majority of people work at a level that is enough to sustain them in their profession. Why improve (or take discomfort) when they’re moving along smoothly. At her typing speed, Matthew Syed’s mother must be surviving well in her job. So why take the pain? Well, such thinking could be naïve. A higher level of the same skill can open bigger doors for you.

We hate discomfort. We enjoy automaticity. And once our behavior becomes automatic, our learning stalls and we stay at the same level.

Top performers understand the role of improvement better than anyone else

Earlier in the post, we looked at how top performers keep improving beyond stall point to reach extraordinary levels. Let’s see few instances of and quotes on improvement from top performers, mostly from sports.

In 1920s, comedian Harold Llyod used a decibel meter to measure how loudly audience laughed at his jokes, a proxy for knowing which jokes worked and which didn’t. He used this data to improve his act and consistently outsold his contemporaries Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton.

However, if he had kept on his act without improvement, he would have had less stellar results despite hard work.

Sanjay Bangar, the batting coach of Indian cricket team, comments how Virat Kohli, unarguably the best batsman in the world of his generation, has reached unscalable heights because of his relentless focus on improvement:

He’s somebody who constantly looks out on an area for improvement and he does that on a regular basis. Probably that’s the reason why he has raised the game to such a level.

Virat Kohli himself says that he moved to power lifting to improve his fitness (something uncommon in cricket) so that he could move to the next level. Listen what he says (duration: 16 seconds):

Marin Cilic says this about Roger Federer, his opponent in 2017 Wimbledon final:

I think his ability and his desire to continue to improve is definitely one of the best in the game. Even at his age now, he’s still improving and challenging himself to get better. All credit to him and his team for finding ways to get him to another level.

And Rafael Nadal, one of the greatest tennis players of all time:

There are people who have talent, but there are others who have the ability to improve. And those who have more capacity to improve are usually those who have more options to succeed. It’s always the same story.

Top performers understand very well that constant improvement in their skills is the surefire way to stay at the top. (Hard work, like I said before, is table stakes. At their level, everyone is working as hard as possible.) That’s why these players have coaches who can point out areas of improvement. However, you don’t need professional coaches for most practical purposes because you aren’t competing to be one of top few in the world.

Summary

Matthew Syed’s mother worked hard for several years, but her proficiency with typing didn’t change much.

The skill level of teachers in North California didn’t change much after two years.

Why?

Because they didn’t seek improvements.

A vast, vast majority falls into this pattern, and they wonder why they’re not becoming world class despite hard work. They aren’t because they aren’t seeking improvements. And the primary reason for that is falling into a routine where they enjoy the effortlessness of the current state. Improvements, in contrast, entail some pain.

You don’t need to practice like the best in the world do. Most of us will be satisfied with, say, a finish in top 1 percent in our goals, won’t we? The key is to keep making improvements, howsoever small they are. (See several examples of improvements from different fields in this post.)

Have you gone bang bang on a goal and worked tortuous hours, but didn’t go too far?